- Home

- Michael Mitchell

Final Fire Page 3

Final Fire Read online

Page 3

My father knows Terrible Taft and was not impressed. Perceiving an injustice he decides to act. An appointment is made and we face down Taft in his office. These two tall men in dark suits angrily circle each other but Taft has all the cards — the seat of office, righteous indignation, ethics and the rule of law. We leave in defeat.

Despite my criminal mind I’m a decent student. The grades of the following two terms carry me through the year and I survive. Taft resigns at year end to take a similar post at a high school in southwestern Ontario. With time my world brightens and the Taft years gutter and die. Another grade passed and I’m free. I get a summer job in the bush and prepare to ride the train all the way to the Pacific where I’ll ferry up Vancouver Island and become a logger. The universe expands.

At Union Station I pay 50 borrowed dollars for a seat from Toronto to Vancouver. Then I pause at a newsstand to buy four days of train reading — with no berth the nights will be long. A huge and very black headline in a big Toronto daily stops me dead. An Ontario high school’s star student having unexpectedly failed his provincial exams has been denied university entrance. Upon appeal his papers were re-evaluated and the failing grade stood. A further appeal has resulted in an inspection of his exam papers and the discovery that they are not his but rather those of the principal’s son. An illicit peek at student papers had confirmed what that principal feared — his son would fail. Some paper palming secured one boy’s future and damned another’s. That midnight switcher had been Terrible Taft.

***

Two-thirds of the run down the river on an overcast day I hit something with a soft thump and the motor quits. I lean over the gunwale and peer into the dark tannic water. The bloated body of a buck hangs in the silty river just below the surface. As I stare it slowly rotates and four legs, stiff with rigor mortis, rise out of the water. The hooves glisten with the wet. The body looks like bagpipes.

1955

The death business has always been with us. My grade six class is being marched down the last street on the edge of town to visit the county’s brand new jail. Our giggling group is led into the processing area and counted before getting a tour of the shiny new cells. Then we are subjected to a lecture about law and punishment. After a pee break we are taken to a final area. It’s a small square room with shiny cream walls and gray lino tiles. There’s a steel-framed interior window on one wall flanked by one door in and another out. Once we’ve assembled two-deep around the room’s periphery the friendly policeman directs our attention to a hook and pulley system centered in the ceiling. Then he points to the floor. A square section of tiles is framed in a metal molding. We are shown how beneath the floor it’s hinged on one side and supported by a sliding bar on the other. Each side of this trap door is as long as our height. Better watch out. We are not shown the rope.

***

When I take my coil of rope down to the dock it is no longer rope, cord or string, it becomes line. I step off the dock into my little sailboat’s cockpit and prepare for my annual spring humiliation. I always do this alone because many friends consider me the one real sailor in their lives. They know that my father had been a ship captain and naval commander. They know that he taught me how to use a sextant, how to splice an eye and tie knots. What they don’t know is that every winter I forget it all and every spring I must sneak off with a book to relearn and practise. So lemme see — a common bowline begins with a loop in the standing part, then . . . And there are bowlines on a bight, the flying bowline, the running bowline, the Spanish and the Portuguese ones and special bowlines used by climbers. There are hitches and bends and lashings and loops. When I have to bypass a line weakness or shorten it I’ll need a sheepshank. My father taught me this one and years of Cubs and Scouts involved me tying hundreds of them but once again I’m stymied. What did I learn in Baden-Powell’s little army?

School 1958

My poor high school classmates: every time we have an essay assignment they have to slouch wearily in their seats and listen to the English teacher read my latest effort aloud to the class. I’d hate me too.

This time the stakes are higher. There’s been a regional essay contest and our teacher has submitted one of mine. It has won. The prize comprehends a little cash and a book. Both are now forgotten but a last-minute addition remains memorable — the judge has invited me to his house. It’s a very pretty white clapboard cottage on a treed lot in a small town on the big lake — Ontario. I arrive alone, bang the knocker and am admitted by a cleaning lady who directs me to the basement. It turns out to be one that’s, as we used to say, “finished.” This means wall-to-wall carpet, acoustic tile on the ceiling and dark Weldwood paneling — a beta version of all the suburban family rec rooms soon to come. This one differs in that wherever the wall space is not covered with framed photos signed by forgotten celebrities, the paneling is obscured by many running feet of sagging bookshelves. I meet the judge and we have a little chat about the writer’s life while I sip a Coke and he has something more adult. When he goes upstairs to answer the phone I scan the bookshelves. The library is very eclectic. It features none of the classics I’ve been taught to admire. Most puzzling is a substantial collection of Hardy Boys adventures and Carolyn Keene mysteries. Why would a grown-up, an established literary adjudicator no less, bother to read these teen entertainments?

When he returns bearing refills for both of us I somewhat jejunely enquire. He changes the subject and describes his life as a young poorly paid reporter for a big city daily in Chicago. My English teacher had always made withering remarks about mere journalists so I was barely listening to his reminiscence when a sentence caught my attention.

He had worked the four p.m. to midnight shift on the news desk. He would then go home to his tiny apartment and while brewing a large pot of coffee open his mail. Twice a month there’d be a letter from the Stratemeyer Syndicate with a flat-fee contract attached to a one-page book outline. He’d start writing by one a.m. and two weeks later mail off the completed book. That’s how Leslie McFarlane came to write a score of Hardy Boys adventure books and the first dozen or so Carolyn Keene mysteries. Now he had the house of his dreams with a finished basement and I had a tiny start.

***

There are low voices on the wind. They’re water on stones, a breeze through pines, the distant gargle of cranes. Footsteps sound along the shore. The waves speak and the wind sings, sighs, whispers and moans many small secrets.

1964

Four of us ran an undergraduate interdisciplinary research project. We — a future physicist, an engineer to be, an upcoming baboon ecologist and me, the anthropologist/archaeologist — planned to sample every drink on the bar menu of the Embassy Tavern’s Starlight Lounge. We were young enough to believe that understanding a zombie, a pink lady or a banana daiquiri was essential adult cultural knowledge. This large room off Bellair just north of Bloor in midtown Toronto was a subterranean, tropical paradise. Its high dark-blue barrel-vaulted ceiling, sprinkled with hundreds of tiny lights twinkling like southern stars, was supported by columns disguised as palm trees. A glowing bamboo bar levitated along one wall while the far end had a stage framed in coco fronds. We’d pay a two-dollar cover, descend the wide stairs and enter this magical place to hear a galaxy of fading stars — the Everly Brothers, Bill Haley and the Comets, Bobby Curtola.

However, for us the main attraction was the drinks menu, a bible featuring numbered illustrations of complex cocktails, their coloured layers oh so lurid and alluring in that basement tropical night. We knew that serious research had to be systematic so we began at page one. Each week we’d work our way through three or four new cocktails. We’d have seconds of favourites to test repeatability. The goal, over a hundred drinks away, was our liquid Eldorado. We never did quite make it.

But for several years we explored global geography via Singapore slings, Manhattans and Moscow mules. One night I showed up with a half-dozen friends to celebrate the birthda

y of finally reaching drinking age. My first legal drink was delivered by the bartender himself as a gift to an established regular — me. On another night we excitedly showed up after an evening class to see Louis Armstrong and his band play our lounge. The cover charge was out of our reach and the place was jammed. All but one of my friends sulked off to the Colonial Tavern downtown. Our remaining sad little party of two slouched into the licensed pool hall a floor above the lounge. We grabbed the last booth at the back and ordered a draft. We were counting our change to see if we had enough for seconds when a deep voice asked, “You boys mind sharing your table?” Louis Armstrong and a couple of sidemen slid into the booth with us and ordered drinks all around. They small-talked with us for 20 minutes before going down the back stairs to play their final set. That lounge is now a suit shop.

During my undergraduate years trudging through slush on King’s College Circle the central visual event was the slow rise of the first TD Centre tower. When Mies’s elegant structure finally opened I went up to the top and was stunned to realize that I could see the far shore of what had always been to me a vast sea. The U.S. was right there, just a hop and skip across a mean and cold pond. It forever changed the geography of my childhood.

Last night I visited that lake in a dream. Its entire shoreline was ringed with 200-storey buildings. My freshwater sea was further diminished. It had reverted to the smelly, stone-shored graveyard for alewives, algae and gray oil-slicked water with a great aggressor looming on the horizon.

Three

Get a Job

“I don’t like work — no man does — but I like what is in work — the chance to find yourself. Your own reality — for yourself, not for others — what no other man can ever know."

Joseph Conrad

Heart of Darkness

1958

“This is the last time that bitch is going out in a powerboat. She’s a fucking squaw so she can drop her big ass in a canoe.” Archie, a crippled-up old white guy, is talking about his wife, Edna. She’s Ojibwa, from the local reserve. Edna had been out all night on one of her binges, drinking and fooling with the boys in town. On the seven-mile trip out of the inlet for home she’d fallen asleep and her old varnished Peterborough runabout had gradually run itself into a weedy back bay and partway up the shore. The tired Johnson 25 had eventually quit so the boat just sat there for hours with its 300-pound cargo slumped in the stern in her latest screaming dress from the Eaton’s catalogue. She really loved her bright colours and beer. That huge wife was some sight moving through the pines in those dresses with her copper skin and shiny black hair.

This was my second summer working for them in their small Georgian Bay marina beside the lighthouse. It wasn’t much. They had a 100-foot dock on cribs supporting a 900-gallon fuel tank and an old Texaco gas pump. There was a rack of plastic 2-cycle oil bottles beside it that I had to look after. Archie would buy a case of them at the beginning of the season. One of my jobs was to make a big show of opening one up and dumping the whole fancy quart into the customer’s five-gallon outboard tank before pumping the gas. It was my responsibility at day’s end to refill those bottles of luxury oil from the 45-gallon drum of bulk utility oil behind the shed. The virgin oil in the sealed bottles was popular with the customers so you had to be careful not to spill on the paper labels. If you were, you could get a whole season of refills out of each bottle. Every cent counted.

At the other end of the dock was their little general store and post office. That’s where I stole the Burnt Almond chocolate bars that I mostly lived on. In this business you got pretty good at sneaking around.

So Archie was as good as his word. A couple of days later he turned up in his ancient inboard utility with a canoe balanced in the cockpit. It was a terrible looking thing — blackened varnish peeled off the gunwales and the canvas was torn and sagging. Got it from an old customer.

“You boys is gonna fix that boat up for the bitch.”

Mike, who was also from the reserve, and a year older than me, stared at that ruin of a boat and then at me. He made a secret face.

“Yer gonna strip her right down, re-canvas and then paint her up. Let the cunt choose the colours.”

So for the next few days Mike and I scraped and stripped between customers at the gas dock. After about a week we called Archie over for an inspection. Passed. He gave us a two-minute lesson on how to canvas and then hobbled off to his post office in the back of the store. You could hear the canceling hammer.

That canvas was sure heavy. We tugged and pulled, tacking it on with little copper brads. When she was all covered over we trimmed the excess. After another inspection Archie gave each of us a galvanized pail.

“Throw water on it and soak her good.”

We did. And the canvas started to steam in the hot sun. It soon tightened right up.

Now for “the cunt and the colours.”

We called Edna over while Archie hobbled off to his stamps. Yesterday her big dress was a cardinal flower. Today’s was someplace between banana and pumpkin. She rocked back on her stumpy legs squinting at the boat. Some gulls called overhead. Small waves broke on the shore.

“I want the gunwales, them thwarts and ribs on that outfit to be coral pink. You can do the canvas in turquoise.”

Mike made another face.

And I was having trouble imagining this — trouble seeing what Edna did. But we’d been ordered to do what she wanted. We both got in our little seafleas and raced off for town. At C.C.’s big general store we bought the paint, a couple of pad eyes in brass, even a paddle. It had an Indian head, headdress and all, burned into the blade.

On the way back out we stopped at the bootleggers for a couple of Molsons. Shit I was almost 15.

We got back to work, selling gas during the morning mail rush, making nice to the girls. We all, them and us, kept our T-shirts and jeans tight. After lunch Archie came out, scoffed at the paint colours but told us to put in on thick. We spooned it on the canvas like plaster — didn’t finish until after eight. As the light failed I cranked up my 10-horse and raced off in my eight-foot boat for our home island. I warmed up a can of stew on my little coal-oil stove and then went to bed in the cabin.

Next morning I was in to work by eight. Islanders later told me they’d know to put the percolator on when they heard me go by each morning. When I got to the marina Archie, Edna and Mike were already staring at the canoe. In the morning light it was really fucking beautiful. Just fantastic.

“Take ’er down to the water.”

We did and that huge woman slipped into it ever so lightly, took the paddle and disappeared. Dress that day was lime green. Try to imagine all those colours together and the blue of the sweet waters, the swept pines and the glittering granitic rocks.

Some sight.

So Edna, having been pretty much fired from her own business, went fishing. That’s all she did for the rest of the summer. We’d see her all over the place in that boat while we were out doing the propane deliveries to the islands. You’d look up while dragging a hundred-pounder up a rock face and there she’d be across the channel, line over the side. You’d grunt the empties into the steel workboat and take way off for the next customer and she’d be there already, line over the side. She was everywhere all at once. It got spooky.

And did she get fish! In a couple of weeks she was a legend with every fisherman on the northeast shore. Small mouth, perch, pickerel and pike, even the odd muskie showed up in the bottom of her boat. Once she came home with a huge sturgeon. And some lake trout. I began to eat better.

I did eventually find out how she got hold of those deepwater offshore fish like the trouts. One full moon night when the wind was up she came whispering over to Mike and me after work. Would we take her out in the big steel boat after Archie went to bed? He always went early on account of the pain in his crippled-up back. We dove for the two-four we kept cold in a dozen f

eet of water off the gas dock and brought up half the case. Then we gave Archie time to fall asleep and the three of us took off with the beers. She showed us how to line up the homemade ranges and get out through the shoals without hitting a rock. When we were a few miles out in the failing light she told us to slow down. There were a bunch of spars bobbing way out there in the big water. We closed on them. Then Edna leaned over the side and began pulling up the neighbor’s gill nets. Those commercial guys had got a good haul of lake trout. We soon had scales all over the deck.

We got back in pretty pleased with ourselves but when I got in to work the next morning and tried to pump gas there wasn’t any. While we’d been out lifting the fish tug crew’s nets they’d been on top of our 900-gallon tank helping themselves. Pretty expensive fish.

***

I have an American neighbour far across the inlet. I dread his arrival because, like the few other Americans in the township, he blows the silence away. Within five minutes of arrival he’s got a gas-powered water pump going. Most Canadians have silent solar ones. No sooner is his water tank filled then he starts a generator so that he can vacuum his log cabin. When the vacuum is full he gets out a gas weed-whacker and attacks the disorderly Canadian wilderness. Then he fills the remaining minutes before dark with a gas leaf blower driving offending pine needles off the rocks of the Shield. Now that his property is under a cloud of two-stroke engine exhaust he vacates to guzzle hard liquor with another sockless giant a couple of hundred feet away. Most of us would paddle there. He roars over in an outboard.

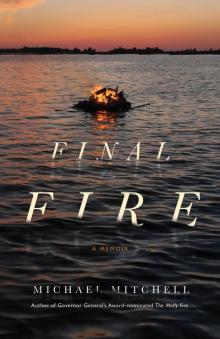

Final Fire

Final Fire